People

Max Hollein on How the Met Will Redefine the Entire Way We Think About Contemporary Art

The freshly installed Met director spoke to Andrew Goldstein about his plans for new art, new technology, and new funding at the museum.

The freshly installed Met director spoke to Andrew Goldstein about his plans for new art, new technology, and new funding at the museum.

Andrew Goldstein

Last Friday, when the Metropolitan Museum of Art announced that it was planning to vacate the so-called Met Breuer three years early, handing the Brutalist building over the Frick in 2020, it was clear that a decision was finally taking shape around one of the most vexing quandaries facing the Met: How can the venerable encyclopedic institution, with works stretching back to the earliest recorded human creations, meaningfully embrace contemporary art without giving off the vibe of a graying relative desperately trying to act cool?

The answer to that question comes in the shape of the museum’s 49-years-young new director, Max Hollein, whose vision for the Met’s embrace of the recent and the now ranges far beyond headline-grabbing shows of evening-sale artists, or even the more sensitive hybrid exhibitions that have been piloted at the Met Breuer since the experiment began in 2016. “Holistic” is a word for his path forward for the museum, and it’s one Hollein uses frequently.

For the second half of a two-part interview to welcome the new director to his role, artnet News’s editor-in-chief spoke to the intellectually nimble museum veteran about where he sees contemporary art fitting in on Fifth Avenue, the expanded role technology will play, and why the Met needs to be “morally sublime” when it comes to securing its funding.

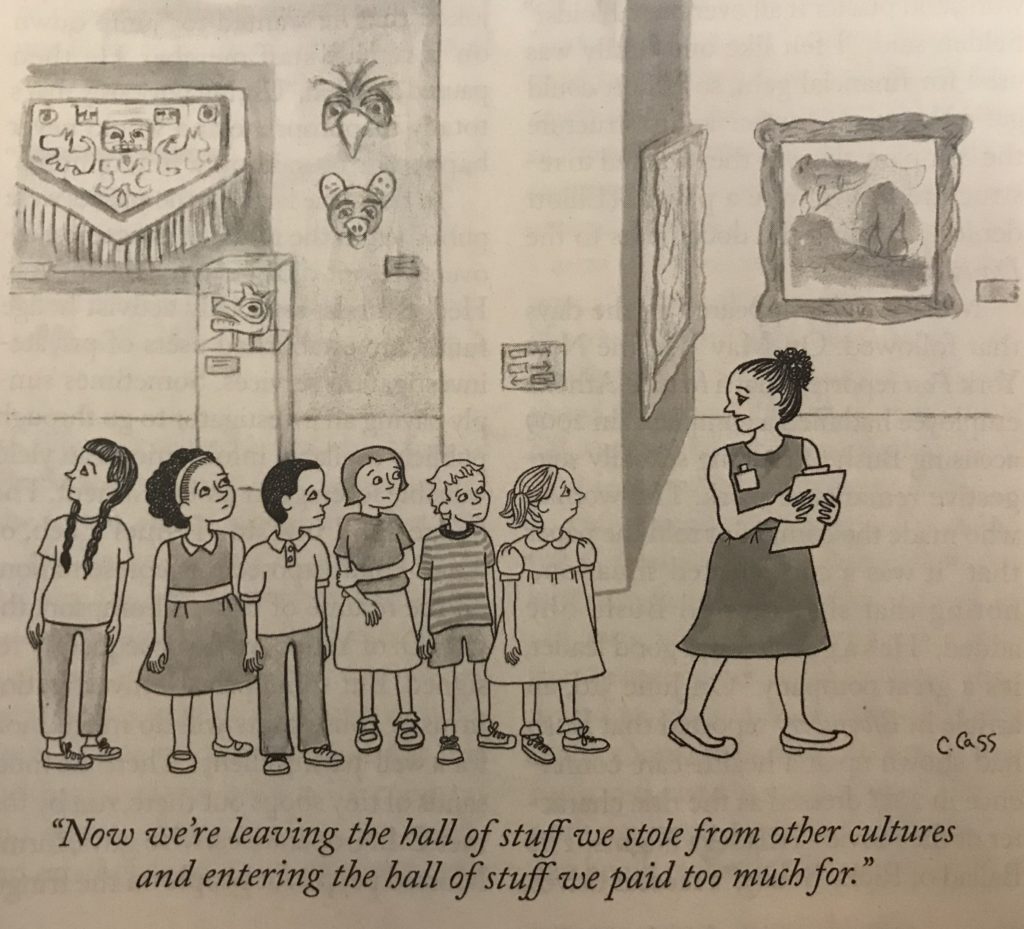

A New Yorker cartoon. Photo by Andrew Goldstein, faithful subscriber.

The New Yorker recently had a very funny cartoon that neatly encapsulated the current museological moment, where a docent leading a group of schoolchildren through a Met-like encyclopedic institution says, “Now we’re leaving the hall of stuff we stole from other cultures and entering the hall of stuff we paid too much for.” Contemporary art has become both a wildly popular mass-culture phenomenon and a supercharged magnet for global wealth. How important is it for an encyclopedic museum like the Met to have a first-class engagement with contemporary art, and how can it be incorporated beyond the way it currently is being leveraged in the laboratory-like setting of the Met Breuer?

First of all, I think there’s a slight misconception: contemporary art was always part of the Met. It started collecting the art of its time in the 1880s and went forward from there, so it’s not a new question. Secondly, it’s important to understand that contemporary art at the Met already resides in many different places. If you go away from the Eurocentric perspective and stop defining contemporary art as just 20th-century European and American art, you would be surprised how many objects in other galleries—like the African galleries, for example—are from the 20th century.

What I’m saying is that if an Asian visitor goes through the Asian wing, they can see contemporary art—you and I, because we share from a certain cultural background, might not see that. So, for me, it’s important to foster a broader understanding of contemporary—not to cater to the market or anything like that, but to better embrace where contemporary art is in our collections without us noticing it. You can create a dialogue connecting contemporary art to the past in a way that you can’t do at other institutions.

The Met Breuer is being used perfectly for that, as a laboratory, as you put it. Some things have been successful there—like Jack Whitten [“Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963–2017,” through December 2]—some have been less successful. But the priority is that Modern and contemporary art is part of the overall narrative in the main building. I would see no long-term benefit for creating a satellite somewhere else in the city.

The Met. Photo courtesy of the Met.

As the son of an architect and husband of an architect-turned-fashion designer, you obviously have a heightened sensitivity to architecture. There has been a plan to create a massive David Chipperfield-designed, $600 million wing for Modern and contemporary art on Fifth Avenue. How does this fit into your vision? And do you see this as a matter of expanding the physical footprint of the museum, or more a matter of refinement and recontextualization?

The answer, as you probably expect, is both. I know David Chipperfield, and I actually will review the plans with him over the next couple of weeks, and then I will have an answer about that. I’m fully for creating enhanced opportunities.

Having said that, to repeat myself, you can also tease contemporary viewpoints out of other collections. I’m not so keen on putting one contemporary piece smack in the middle of the Greek and Roman gallery and saying, “Well, here is a dialogue.” That’s not what I’m talking about. I think it’s a question of contemporary art, but also contemporary perspectives, and finding the contemporary in some places around the museum where you might not expect it.

I once did a show with the art historian Raphael Rosenberg that was called “Abstraction,” and it showed work by Victor Hugo, Gustave Moreau, and late J.M.W. Turner. So it showed you abstraction before anyone was even talking about abstraction.

When many people think about contemporary art, they think about artists like Damien Hirst, whose shark is at the Met, and other heroes of the art market. You have a more sensitive way of talking about it, where it’s more about contemporary thought. Your predecessor, Thomas Campbell, had difficulties in the past where the staff was worried about the reallocation of budget toward a splashy engagement with contemporary art, and away from the more historical departments. Have you been able to reach out to the staff about your ideas? And how do you intend to engage them in your program?

In fact, I gave my first presentation last week to what we call the “Forum,” which is the entire group of curators, conservators, and scientists, and I’m doing another one tomorrow to present a more fleshed-out version of what we were just talking about and how it ties into initiatives that are already on their way. I am almost too immersed in contemporary, so I want to make clear that having a contemporary sculpture pop up in the middle of a department is not what’s going to happen. I’m much more interested in fostering a spirit of collaboration, and you will see that it will be a much more interwoven and interesting formulation.

A view of the Minecraft recreation of the famed pyramid from the “Teotihuacan: City of Water, City of Fire” exhibition at the de Young. Image courtesy of the de Young.

Together with the rising popularity of contemporary art, advances in digital technology are one of the most important developments reshaping the landscape for museums today, making them as much virtual institutions as brick-and-mortar ones. You’re coming from San Francisco, the crucible of the American digital revolution, where you made inroads with the tech community and were known for such celebrated coups as including a Minecraft map of an ancient Mesoamerican pyramid in the 2017 exhibition “Teotihuacan: City of Water, City of Fire.” What are the opportunities you see for the Met in the digital sphere?

The Met has been a leader in digital projects more or less from day one. So what I’m going to say builds on a very substantial, robust program. It is important to acknowledge that the museum is not just a physical space—a museum is about the dissemination of knowledge, education, and an understanding of culture to a wider audience than could ever physically visit us. So digital platforms give us tools to properly scale our educational initiatives, for storytelling, and reaching out to audiences.

It can do this in two ways. One is that it can clearly enhance your visit—for example, one thing we implemented in San Francisco was called Digital Stories, which were 30-minute multimedia online courses that gave you a deeper understanding of the context of an exhibition. When you bought an online ticket, we sent you the online course for free, basically saying that you might have a richer experience if you watched it before coming to see the show. So, digital can enhance the quality of a visit, which is something the Met has already been doing with its Timeline of Art History, and it also helps us reach a huge audience.

To further amplify that will be one of our core missions. If you define the Met as a museum that represents the entire world through our collections, then it should also ideally be a museum that caters to the entire world. We will pursue that on multiple fronts, including partnering with existing platforms instead of building everything up ourselves—this is something I already worked on in San Francisco.

Then, on the other hand, digital is also a tool to help us improve your visit in terms of online ticketing and if-you’re-interested-in-this recommendations, which goes more into CRM [customer relationship management] system ideas. But I think it’s the storytelling and narrative part that is really interesting.

When you bring up the idea of being an educational institution, it raises an interesting, almost philosophical issue at a moment when experts and institutions are have come under attack for the very authority they represent, while at the same time studies by Culture Track reveal that audiences have begun to show a preference for fun social art experiences that entertain and delight, rather than the traditional ones that demand, challenge, and educate. The Met, of course, is the very apogee of the expert, educational art institution. Do you think the Met needs to change its relationship with the viewer in any way to accommodate shifting tastes?

I don’t think so, and I also think it might be a misunderstanding of my use of the word “education” that triggered your question. You can be a very dynamic institution that engages its visitors or users and still teach people new things, because it can be fun to detect the meaning of a particular object and how it connects to one’s life.

The feeling of being part of something starts with knowledge. For example, people come to an exhibition more or less unprepared—whereas if you go to a baseball game, the audience is very prepared, they know the batting statistics of the players, et cetera, so they feel it’s engaging. Earlier I discussed making it clear that objects are being exhibited for their aesthetic or art historical merit, but that they also have a very complex social, political, economic, and historical framework. Making that more transparent and engaging can be something that really resonates not only with existing constituencies, but also with the new audiences that you referenced from the Culture Track studies.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo courtesy of the Met.

On a less high-tech level, to go back to your success with “Teotihuacan,” you also translated all of that show’s press materials into Spanish. How much of a priority will it be for you to reach out to new audiences at the Met, and what new audiences do you think remain untapped for the museum?

We translated the materials for the show into Spanish to engage the Mexican community in San Francisco—but I actually used this as a starting point to say, “OK, from now on, we’re going to work more with the Mexican community in San Francisco.” So that meant that materials for an upcoming Monet show should be translated into Spanish too. I don’t want to only reach out to communities when what you’re doing touches their own culture—it’s really about taking communities seriously as a whole, in the same way that I, as an Austrian, don’t only want to be called when there’s a Gustav Klimt show. It’s really a multifaceted and holistic approach, some of which we are already pursuing at the Met, in that we are offering tours in different languages. But we can do much more—and here, again, digital dissemination offers a huge number of possibilities.

You speak about engaging audiences—what would you say is the key value proposition that the Met should convey to its audience to get them to visit rather than go to a Yankees game?

I want the Met to have a strong voice in the cultural discussion. That doesn’t mean entering into any political debate, but rather making clear that a cultural institution is not only a place where you can see the greatest artistic achievements of mankind, but also where you can enter into a fascinating, complex cultural dialogue about yourself and your place in the world. That’s something we need to stand for, and something we need to clearly communicate. The more we can project that voice—and not in an authoritative way, but rather an engaging and inviting way—the more it will become equally, if not more, exciting to come to the Met as to a baseball match.

One admirable element that stands out in your track record is that you are able to think of the curatorial side and the business side as two sides of the same coin. Now that you are at the Met, Dan Weiss is going to primarily be in charge of the museum’s business affairs while you lead the curatorial operation. Is that a proper way of describing it? How would you describe the way your roles work together?

I think that describes it. On the other hand, both of us look at the institution holistically and also see this leadership structure as a partnership. We had several conversations during the search process where both of us said it’s to our great advantage that we have experience that allows us to look at the institution in an encompassing way. I’ve been the director of an institution since I was 31 years old, and I’ve always looked to realize its most exciting and sometimes wildest programmatic dreams while still maintaining a financially responsible position. And Dan, on his side, has done that as well. The Met is clearly the most complex institution in the museum world, so it’s great to be able to divide up certain responsibilities—especially for me, because it means that I can really focus on the programmatic side, which is what the Met needs to keep moving forward. We are in clear alignment on that.

The Temple of Dendur in the Sackler Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo courtesy of the Met.

What is the most common exhortation you’ve heard from your meetings with the board so far? Anything that comes up again and again?

The board impressed me tremendously in terms of the time they devoted to the search. It would be hard for me to boil the conversations down into one single element, but clearly the board believes that the Met is the banner-carrier of encyclopedic museums, which comes with an enormous obligation to be there for an audience that reaches way beyond New York. The board feels that the Met doesn’t need to change—but it needs to continue to evolve and reshape its offerings according to its idea of what an encyclopedic museum in the 21st century should represent. That’s really what drives this institution—to continue to foster deep knowledge, scholarship, and collection excellence, but also to present a multifaceted but highly formed narrative of cultural development and the intersection of cultures, and to do so in the world’s voice.

You are renowned as an inspired fundraiser, which is a skillset that will come in handy at the Met, which is coming out of a dark financial crisis and is is working to rebalance its budget by 2020.

Fundraising is part of any director’s job, and I have been involved in fundraising from day one of my museum career, and more importantly when I was running the Städel Museum. The Städel is actually the oldest and most important private cultural foundation in Germany. It’s 200 years old, and it’s kind of the blueprint for the American museum model. So I’ve been involved in fundraising for capital projects, for operational needs, throughout the years. I see fundraising as a huge opportunity to communicate your priorities, to set an agenda, and to bring people along. I couldn’t think of a better place to continue to do that than at the Met, where you have such a dedicated group of supporters both on the board and around the museum.

Occupy Museums performs Purification of the Space – Ritual Rebranding of the David H. Koch Plaza on the Day of its Dedication Photo: Courtesy of Erik McGregor

Your combination of skills suggests that there are many opportunities for fundraising for the museum. At the same time, this also contains some degree of peril, since, as we have seen, sources of revenue at cultural institutions have come under fiery scrutiny of late, from the Sacklers to the Koch brothers. Is this something that you think the museum needs to take to heart when it’s looking to balance its budget and identify new sources of funding—the demand from certain quarters that it live up to high moral standards?

I think that it’s clear that if you are one of the leading museums in the world, if you have a very strong voice in the cultural discussion, that means that you have to have a morally sublime attitude not only about how the institution is set up, how it operates, how it is providing its services to the community, but also that its fundraising and funding is based on a clear set of values that we project. And I have not seen the Met not doing that ever since I looked at it, but it’s clearly going to be a guiding principle for us going forward in the future.